Universal Credit

8th April 2017

A focus on tenant wellbeing

8th April 2017The uneven impact of welfare reform: challenges for the housing sector

The Coalition Government instigated a major overhaul of the welfare system in 2010 which has dominated contemporary political, economic and policy debates in the United Kingdom ever since. Professor Christina Beatty of the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University, outlines the scale of these reforms, as well as the current and future implications for Northern Ireland.

The direction of travel in terms of both the scale and breadth of the reforms underway since then has been continued by the successor Conservative Government which took office in 2015. Welfare reform is central to the Government’s deficit reduction plans and has led to substantial reductions in eligibility and entitlement across a whole array of working age benefits. The stated aims of the reforms are to create a ‘fairer’, simpler system which continues to protect the vulnerable.

Essentially, the totality of the reforms creates a downward pressure on the level of benefit income available to working age families and is ultimately being operationalised as a job-activation tool to incentivise work and make work pay. A rights and responsibilities agenda is also being promoted which enforces higher levels of conditionality as a requirement for receiving benefits. As a consequence, the scale and purpose of the welfare state is being fundamentally challenged, especially in relation to the public housing system, as the level of Housing Benefit or type of housing which is available to working age households on low-incomes is being questioned. The impacts are wide ranging and affect those receiving benefits due to long-term sickness or disability, those in low-paid or precarious work, as well as the unemployed and indeed the children within these families. The impact of the reforms is very uneven across different places, household types and by tenure.

This article updated evidence drawn from research undertaken by the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research at Sheffield Hallam University on ‘The Uneven Impact of Welfare Reform: The financial losses to places and people’ which was co-funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and Oxfam.

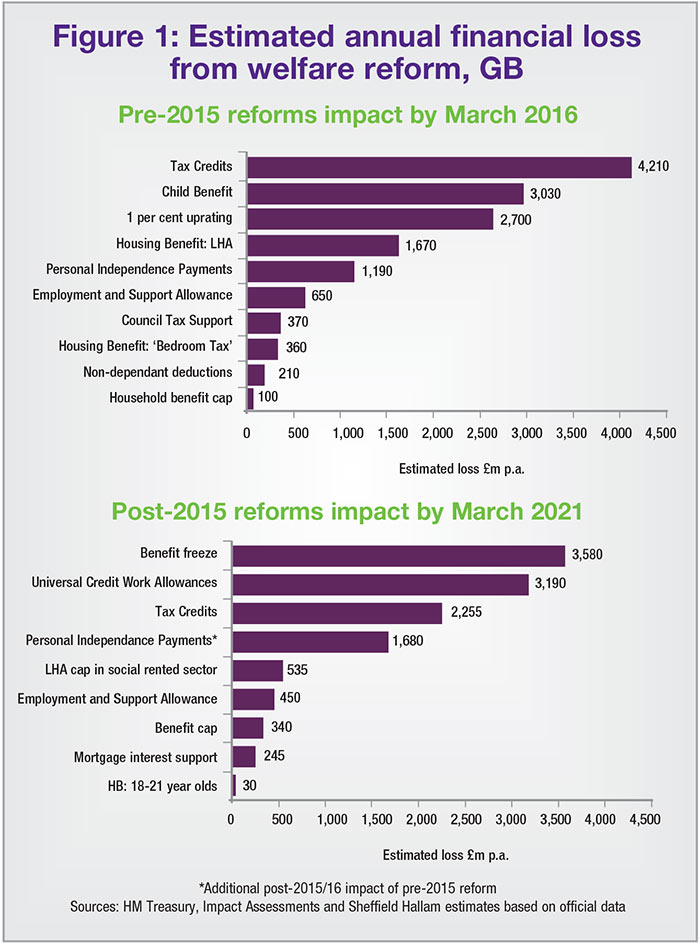

Reform package in Great Britain

The scale of the changes in Britain are significant in both parliaments and include 18 major reforms overall (Figure 1). In addition, the Universal Credit system for a single real time payment system covering all income-related working age benefits is being introduced. The pre-2015 reforms equate to cuts of £14.5 billion per year by March 2016 and an additional £11.7 billion per year cut by early 2021. Claimants are therefore expected to have lost a cumulative total of more than £26 billion a year as a result of the welfare reforms implemented since 2010. This is the level of additional support that would have been available to low income families had the reforms not have been made. This is rather more than £1 in every four previously paid to working-age benefit claimants and equivalent to £660 a year for every adult of working age (claiming benefits or not) across the whole of Britain. The scale of cuts is unprecedented and impacts on the local economies of the communities where those affected live, as well as the individuals themselves.

The reforms include attrition in the value of working age benefits over both periods due to lower than inflation uprating initially and then a four year freeze the value of benefits – this is especially pertinent as we head into a higher inflation period in the wake of the Brexit vote. Tax Credits for families in low-paid or precarious work, and disability benefits paid via Employment Support Allowance or Personal Independence Payment have also been reduced. Changes to Universal Credit, which is introduced in Northern Ireland from September 2017, reduces the amount you can earn (Work Allowances) before support starts being removed. Reductions in the level of support available via various aspects of the Housing Benefit system for both private rented and social rented sector tenants have also been introduced. Details of the reforms and the average amount lost by those affected can be seen in the full report.

Challenges for Northern Ireland

Since 2010, as the legislation to implement the reforms has developed, the process in Northern Ireland has become unbuckled from the delivery of reforms in Great Britain. Certain flexibilities and a package of funding until 2020 to mitigate some of the effects of the reforms being introduced from 2016 has been agreed by the Northern Ireland Executive. To all intents and purposes this means the majority of the reforms in Northern Ireland are at a less advanced stage than in Britain.

However, due to parity in social security provision some measures are already in place in Northern Ireland, such as the reforms to the Local Housing Allowance (LHA) system of Housing Benefit for tenants in the private rented sector. This one reform reduces funding by over four times the amount as via the ‘bedroom tax’. Other reforms such as the uprating and freezing of benefits, and the initial pre-2015 Tax Credit reforms have also been introduced.

Legislation to introduce an LHA system for setting Housing Benefit entitlement in the social rented sector to be capped at the equivalent of the lowest thirtieth percentile of private market rents is also imminent. This is likely to have big implications for rental incomes for housing providers in areas with low market rents. This reform will also mean having to apply LHA occupancy rules for single tenants aged under 35 in the social rented sector reducing eligibility of Housing Benefit to the Shared Accommodation Rate rather than the level applicable for a one-bedroom property.

If the full reforms are eventually introduced in Northern Ireland without continued and extended mitigation, as is the case in much of Great Britain, this will lead to an increasing marginalisation of particular sub-groups of tenants, including the young, the vulnerable and within particular housing market contexts. Families with dependent children will also be hit particularly hard especially lone parent households with more than two children. In Britain half of the financial losses of the post-2015 reforms fall on tenants in the social rented sector.

The British experience has also shown that the impacts are very uneven across the country with the poorest parts of Britain hardest hit. This relationship holds both across and within local authority areas. It is the places with weak labour markets, limited job opportunities and a preponderance of low pay jobs which bear the brunt of the reforms and indeed the working age people living within these local areas.