Further education and training (FET) at the forefront of future green skills in construction

7th November 2024

How research can shape effective housing policy

7th November 2024A European housing policy perspective

Dara Turnbull, research coordinator at Housing Europe, compares the housing context in Ireland with exemplar EU member states.

Speaking on behalf of Housing Europe, the European federation of public, cooperative, and social housing, Turnbull unpacks Delivering on housing in Ireland: A European policy perspective. Commissioned by the European Parliament’s Renew Europe group, the report examines the context of the State’s housing sector relative to other European states and offers potential solutions for decision-makers.

Ireland’s housing crisis has several elements, but the most consistent theme is that the cost of housing is outweighing wage growth, thereby making home ownership and rents inaccessible or unaffordable for many Irish residents.

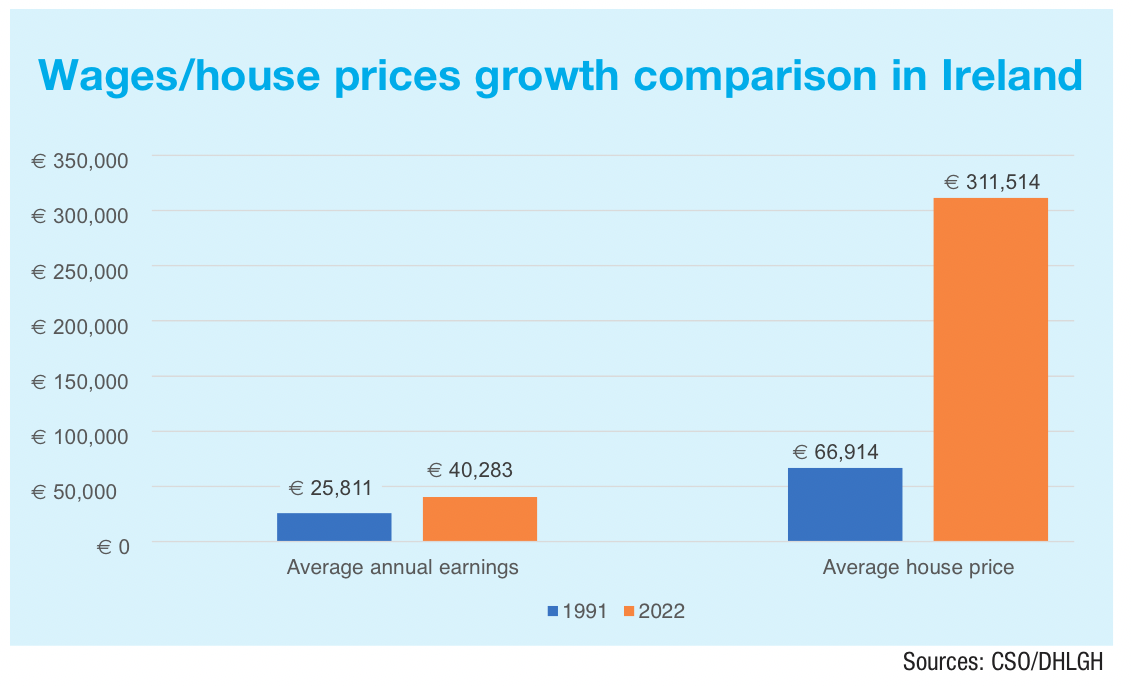

For prospective homeowners, for example, statistics from the Central Statistics Office (CSO) and the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage, show that the average house price increased from €40,283 in 1990 to €311,514 in 2022, a growth of almost a factor of seven or a 673 per cent increase.

Meanwhile, the average annual earnings in the Republic in the same period grew from €25,811 to €66,914, a 159 per cent increase. This disparity between wage growth and house prices has meant that, whereas in 1990 the average house price was around 56 per cent higher than annual earnings, house prices are now around 4.65 times greater than annual earnings.

Supply shortfall

Housing Europe’s report determines that Rebuilding Ireland, the Irish Government’s previous housing strategy, had a goal of building 25,000 new homes per year, but that “actual output was only around 76 per cent of that”.

Although the housing crisis is being exacerbated by undersupply, delving into these building statistics, Turnbull asserts that the area of most significant underdelivery was primarily in private sector construction.

“A relative overdelivery by the public sector has helped to compensate for an underdelivery by the private sector,” he says.

“Government needs to be more aware of the direct policy levers that it has over public housing policy versus demand side incentives and schemes which are not necessarily leading to delivery of infrastructure.”

Affordability disparity

Examining Ireland’s housing market compared to those of Austria, Denmark, and the Netherlands on housing affordability specifically, Turnbull explains that in Ireland in 2022, around 9 per cent of the total housing stock was classified as social and affordable housing. This figure is significantly below figures of 24 per cent in Austria, around 20 per cent in Denmark, and just under 30 per cent in the Netherlands.

Comparing Dublin with the exemplar state’s capital cities, Turnbull states that the “disparity is even greater”. Around 11.3 per cent of Dublin’s housing stock is classified as being “social or affordable”, while this figure surpasses 40 per cent in Amsterdam and Vienna.

The Housing Europe research coordinator explains that this disparity may well be down to the European practice known as ‘build and retain’. “They build social housing and the objective is to retain the system in perpetuity,” he outlines.

Contrasting this model with Ireland, Turnbull states: “The majority of publicly supported and publicly built housing that we have constructed in the State since the 1930s is now privately owned. We have been very good at building public housing in this state, but we have not been very good at holding onto it, so that is a missed opportunity.”

Meeting cost challenges

To meet the challenge of under delivery by the private sector in housing supply, Turnbull cites a cooperative model utilised in Sweden which could be adapted for the Irish market.

Essentially based on what Turnbull describes as a ‘cost purchase’ principle, the Swedish model is backed up by a national cooperative housing guarantee fund, which enables newly forming local housing cooperatives to unlock the necessary construction loans from commercial banks, which would otherwise not be possible given a lack of collateral to ‘back up’ such lending.

“A local housing cooperative can come together and pool their resources to build new housing. When the development loan is repaid, that lending is refinanced as standard mortgage lending,” Turnbull explains.

As a result, around one in four Swedish primary residences are part of the cooperative housing sector.

Housing for All

In 2023, the Government met its overall housebuilding target under its Housing for All policy of constructing 30,000 homes, and Minister for Housing Darragh O’Brien TD has expressed his confidence that a similar number will be achieved in 2024.

Turnbull warns of a potential “dark cloud” for construction, as the raising of interest rates by the European Central Bank may prevent private construction from playing an optimal role in house building due to prospective inadequate yields.

As interest rates are likely to reduce through the course of 2024 as inflation is projected to decline, there may be long-term optimism that supply will increase in the Irish housing sector which is the ultimate key to solving the state’s housing crisis.

However, Turnbull states that even if interest rates do decline towards the end of 2024, or in early 2025, they will nevertheless be much higher than in the preceding decade. Thus, other investment will remain more attractive, meaning real-estate will not be as attractive as prior to the ongoing inflation crisis.

He continues: “Given strong protections for tenants, which are completely justified, the long-term return on things like build-to-rent are not as attractive as in the past, when there was effectively no clear limit to potential returns. As a result, the capital value of BTR apartments is today, and will remain in the future, below the actual cost of construction. This effectively means that such projects are not viable.

“Even if interest rates decline, it does not suddenly mean that residential construction kicks back into gear. I think the dark clouds over the sector will not lift so easily. Having said that, it seems that in the Republic, large Approved Housing Bodies have become important purchases of residential developments that had originally been earmarked for large corporate investors.

“The State may be able to pick up some of the development already in the pipeline, but it is not clear how this pans out over the longer term,” he concludes.

| Dara Turnbull Dara Turnbull is the research coordinator at Housing Europe – the European federation of public, cooperative, and social housing, where he has worked since 2019. He is responsible for managing various research projects, and working to promote the uptake of new approaches and best practices by housing providers. |