Coillte: Promoting wood as the sustainable building material of the future

3rd July 2024

Age-friendly housing: Meeting the needs of Ireland’s ageing population

3rd July 2024Bigger barriers to housing development than finance

Project viability, not access to finance, remains the primary challenge to residential development, a government appointed investment group has reported.

Funding of land without planning permission; funding apartment developments which do not have a committed purchase from the State; and funding projects which require significant infrastructure development, are highlighted of examples of some of the viability challenges currently being faced in residential development.

However, the report says that while viability remains a challenge in certain segments, reasonable access to finance for viable development does exist.

The Report on the Availability, Composition and Flow of Finance for Residential Development was delivered by the Department of Finance, following the establishment of an Investment Workstream group to carry out a priority action of Housing for All.

Noting the impact of increasing interest rates in the past 12 to 18 months, particularly, the cost of funding, the report says that stakeholder feedback suggests this is only having a “marginal” impact on viability, and is not causing residential projects to become unviable as a standalone factor.

Highlighting the increased role of approved housing bodies in providing funding to developers through the construction phase of delivery, the report says that while this has previously been a feature of the funding market, momentum has been growing over the past year and is growing in scale.

This has made for an “active funding market” for social and affordable delivery, with strong competition to provide funding from domestic banks, secondary and alternative lenders, the Land Development Agency, and approved housing bodies.

Highlighting feedback that the increased role of approved housing bodies to provide construction phase funding has served to reduce total overall acquisition costs for the bodies, the report adds that by eliminating any private financing costs (debt and equity), the process can make high density developments viable, and can allow AHBs more control over the design process.

However, it also outlines that all stakeholders identified that such an approach redistributes risk from the developer to the funder, meaning it “requires expertise and close monitoring of development projects”.

Uncertainty around planning was identified as one of the largest risks to future development. While stakeholders identified recent changes, and await the enactment of the Planning Bill, all noted that “significant risks and uncertainties remain” and that “the risks involved in taking a project through the planning cycle is inextricably linked to the availability of capital”.

Indicating a lack of lender appetite to fund land without planning permission, the report says that planning process timelines, as well as judicial review and the de-zoning of land risk all impede the delivery of new homes.

The outcome, some stakeholders suggest, is a “two-tier land market” in operation. “There is heightened competition for land which has planning permission, and consequently there has been no resetting of land prices in this segment. This is also supported by the activity of state or state-backed entities in progressing projects which have planning permission in place,” it sets out.

Another risk identified is the significant upfront cost placed on developers associated with infrastructure development and the provision of utilities. The Department states: “In relation to the provision of infrastructure, debt and equity providers have limited appetite to fund long-term projects that require extensive infrastructure as this infrastructure can take many years to complete, prior to any homes being constructed or sold.”

Adding: “A number of stakeholders also identified the impact of delays with the connection of utilities, in particular water and electricity, as this extends the timeline of delivery of projects, which in turn increases costs for developers.”

International investment

Noting feedback that international institutional investment in residential development had been lower during 2023 than in previous years, the report acknowledges a global reduction of private rental sector activity “in a meaningful way”.

Feedback pointed to the 2 per cent rental cap and policy uncertainty as key themes raised by investors as potential deterrents to investment. However, those consulted surmised that Ireland remains attractive for investment generally, given the strong demand and demographics, particularly for rental market products.

Funding requirement

The report, published in June 2024, assesses the level of development finance that will be required to deliver on the current annual Housing for All target of 33,000 homes to 2030. However, these figures are subject to change given the Government’s commitment to publish a revision of the National Planning Framework later in 2024, which will include an increase of housing targets.

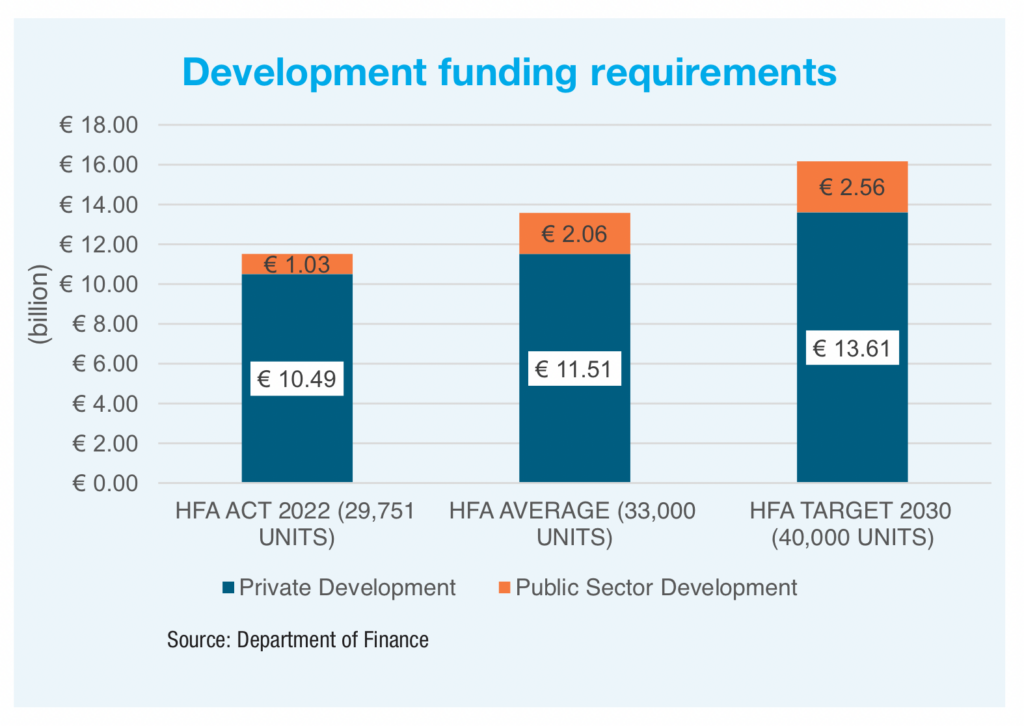

Offering a breakdown of the composition of development finance in the market in 2022, the Department calculates that the 29,751 housing units completed required development funding, both public and private, of about €11.4 billion.

The modelling estimates that €13.6 billion of development funding will be required per annum, the majority of which (€11.5 billion) will be required from private capital sources to maintain the 33,000 homes per annum target. These figures are the result of a modelling update carried out in December 2023 to reflect increased in the cost of construction of a house and an apartment.

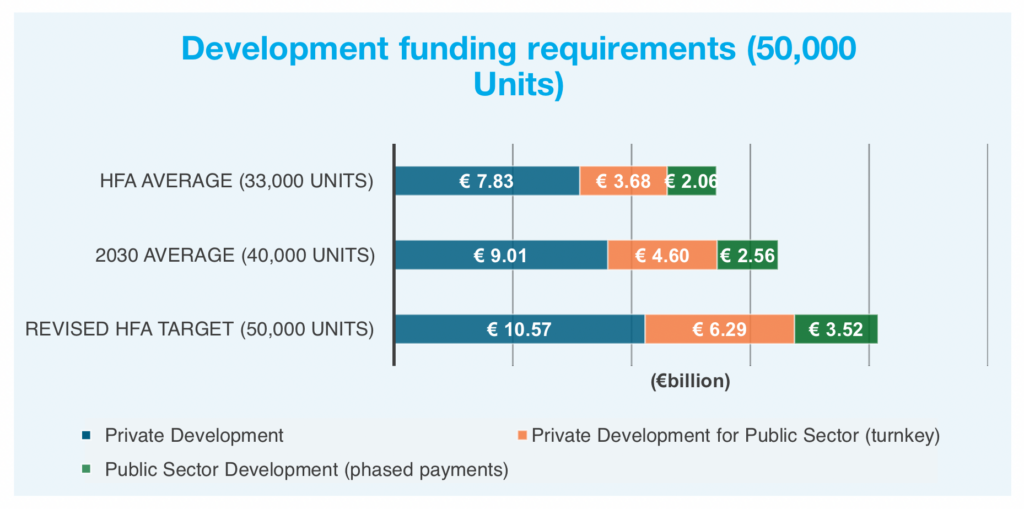

If the supply of housing was to increase to an average of 40,000 units, estimated development funding of €16.2 billion would be required, of which €13.6 billion will need to come from private capital sources.

A target of 50,000 units would require almost €20.4 billion in estimated development funding, €16.9 billion from private capital sources and €3.5 billion from the public sector. The Department attributes the significant jump in public funding under the 50,000 unit scenario to “the increased costs in funding apartment development”.

The report states: “All stakeholders emphasised the importance of attracting private capital alongside public investment, and that in order to maximise the impact of State investment, any interventions should be co-designed in collaboration with the private market.

“In so doing, private capital may be leveraged alongside public investment, ensuring that not all the burden, risk and cost is placed on the State.”