RTÉ sells part of its Montrose site for housing: the price €107 million

19th July 2017

Measuring liveability

19th July 2017Digital housing

Chief Executive of the UK’s Halton Housing Trust, Nick Atkin, outlines the driving factors behind his organisation’s Digital First strategy and the benefits it brings to both the business and the customer.

The assumption that people who live in social housing don’t have access to the internet is a lazy myth according to Nick Atkin. Having spoken to over five and a half thousand customers in Halton’s 7,000 homes, he found that over three quarters have access to the internet themselves and a further 12 per cent know where to get access to the internet, be it in a public library or with friends or relatives.

At the heart of the Digitial First approach was the need to rethink the way services were delivered to prepare for the introduction of Universal Credit in England. Previously, housing benefit was paid directly to landlords, but under Universal Credit, benefits are now paid directly to the customers, who are then required to pay their landlord. In the case of Halton, they found that they would now have to find a way to collect 65 per cent of their income, which they were used to receiving directly.

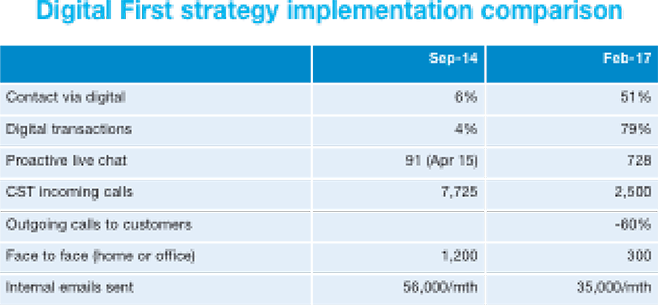

The growth of internet accessibility was a key factor in Halton’s drive to offer their services digitally and saw them set out ambitious targets in 2015 to ensure that 90 per cent of all customer generated transactions would be delivered through online self-service routes by 2018. The decision, according to Atkin, was driven by the financial reality that the average cost of one in-person transaction for the Trust was £15, starkly contrasting with the 10p average cost of a self-service digital transaction. Atkin adds proudly that Halton have reduced that further to just 3p for their own service.

“We are having to transform our services to respond to spiralling arrears, most of which are Universal Credit based. To collect 65 per cent of our annual income, which for us is around £25 million, we were faced with the choice of either employing lots more people or moving resources from non-value adding transactional type activity to supporting and getting money in where it needs to happen.”

Atkin explains that the most successful element of their digital transition by far has been their app, which is tailored to ensure the customer can access their required service in three clicks. To date, Halton estimate that over 95 per cent of the services which their customers contact their landlord for, on a daily basis, can be resolved online.

“The switch to digital requires a shift in psychology. If people are going to switch to self-serve there must be an incentive for them to do so, the system must be trustworthy and effective. If you get the system right, then our experience clearly demonstrates people will choose to switch to digital provision in their thousands.”

“The switch to digital requires a shift in psychology.”

Among some of the key “lifeblood” statistics which Halton use to assess their service, Atkin points out that contrary to the common belief that people prefer to deal with people, customer satisfaction levels for Halton are the highest they have ever been at 95 per cent. Other interesting figures show that, as of January 2017, 76.4 per cent of customer led transactions are now digital and that calls to their centre have reduced by 75 per cent over three years. This has led to half the number of people working in their contact centre compared to just 12 months previously.

Concluding, Atkin points to five key questions housing providers should put at the forefront of their plans to switch to digital:

1. What are your digital aspirations?

2. What buy-in do you have from your executive team and board on your digital aspirations?

3. What plans do you have to reduce the availability of some services to discourage customers who are digitally competent from contacting you in the more traditional or less cost effective ways?

4. What is your organisation’s approach to mobile, flexible/agile working?

5. To what extent is digital embedded as a key enabler in your organisation’s wider strategic plans?