Peter McVerry Trust plans significant growth in housing delivery

1st June 2021

Respond: Growing from strength to strength

1st June 2021Homelessness during and after Covid-19

Austin O’Carroll, HSE Clinical Lead for the Dublin Homeless Covid Response, discusses the challenges of coordinating homeless services during the Covid-19 pandemic, how cross-sectoral collaboration was key to lower-than-expected infection rates, and the future of homelessness services after the pandemic.

“I live and work in the north east of Dublin’s inner city,” says O’Carroll, a GP who was also a founder of both Safetynet, which provides GP services for 6,000 marginalised patients annually throughout Ireland, and GMQ, a primary care programme for homeless people. “I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the north inner city was the epicentre of Covid infections in the country. Covid, as we might have expected, is affecting areas of deprivation the most.”

As the crisis began, Mike Ryan, Executive Director of the World Health Organisation’s Health Emergencies Programme, warned governments: “Be fast, have no regrets. You must be the first mover. The virus will always get you if you don’t move quickly. Perfection is the enemy of the good when it comes to emergency management.” These words guided O’Carroll and his colleagues as they sought to protect the most vulnerable in Irish society.

“We’ve seen an incredible collaboration between the HSE Social Inclusion team and the Dublin Region Homeless Executive [DRHE] along with Homeless Accommodation Providers, specialised clinical services, addiction services and harm reduction organisations. We developed this collaboration to address the Covid response but, actually, it has provided a lot of opportunities to address homelessness into the future,” O’Carroll says.

“Very early on, there was a huge flurry of activity amongst homeless health services because there was a palpable fear about the effect of Covid on the homeless population. As you go through the slope of inequality, as you go through poverty into lower socioeconomic groups, basically all health indices get lower and mortality rates get higher, while illness rates and crime rates get higher. However, when you reach homelessness, it’s like you hit a cliff face, the cliff edge of inequity. Mortality rates shoot up, as do the rates of illness.”

International research shows that mortality rates among homeless people are between 3.5 and 40 times greater than among the general population. Research undertaken by O’Carroll and Safetynet General Manager Fiona O’Reilly in Dublin outlined the poor health profile of people experiencing homelessness. Key findings include:

- one-in-33 homeless people have HIV;

- one-in-four have hepatitis C;

- one-in-three have attempted suicide at some stage in their lives (one-in-10 over the last six months);

- 13 per cent have a diagnosis of schizophrenia;

- 30 per cent are heroin users;

- 41 per cent drank alcohol above recommended limits; and

- in terms of access to healthcare, 25 per cent don’t have a medical card despite being entitled.

With such health challenges abounding, the flurry of activity necessitated by the Covid crisis needed to be a coordinated. “First of all, if a hostel manager identified someone who was symptomatic, they would ring up the Covid response team (staffed by HSE, Ana Liffey Drug Project and Depaul) who would arrange for Safetynet to triage (and if required) test them and move them straight away to isolation,” he says, describing the process by which Covid was tackled among the city’s homelessness services.

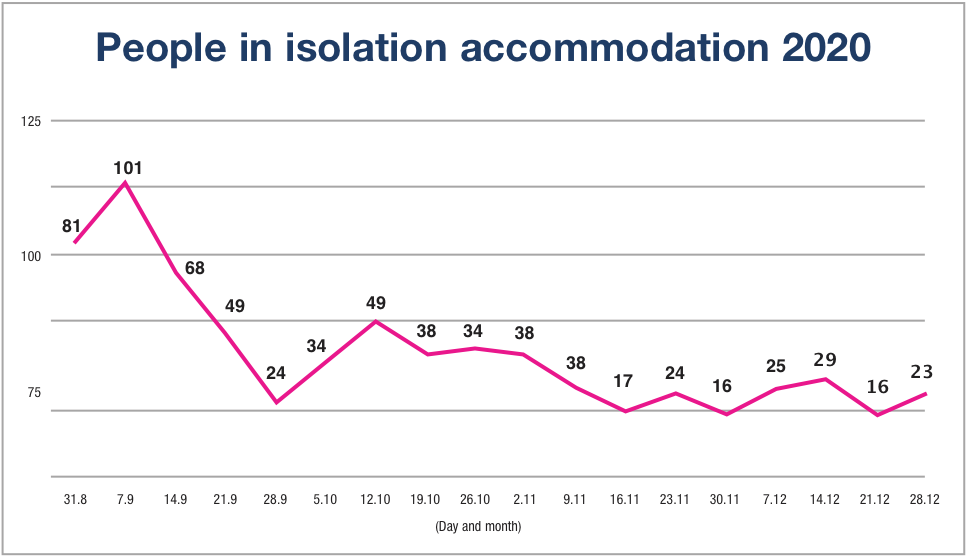

“If the accommodation was suitable, some of the people would isolate where they were situated, but the vast majority were moved. We were quite strict on this on the basis that we didn’t want the virus getting into hostels. DRHE came up with a lot of accommodation including a 100-bed unit in St Augustine’s. It is comprised of 100 two-bedroom apartments into which we would isolate people. The McVerry Trust provided staff and nursing support. Depaul Trust also had a unit in Clontarf. The accommodation providers would provide the staff and nursing support while Safetynet would monitor the patients to make sure they didn’t become too unwell and need to be moved to hospital.

“We came up with this model whereby we would identify the most medically vulnerable and put it into place. We pursued identification through a scoring system based on age and medical vulnerability. For instance, you would get a point if you were 40-50, two points if you were 50-60, three points if you were 60-70 and four points if you were over 70. If you had diabetes, you’d get four points, if you had chronic heart disease, you’d get two points, etcetera. We identified the risk diseases and give points based on that. We came up with the points scale between two and 13. We identified a lot of these people who were already in their own room and had access to their own rooms and could isolate and keep safe. DRHE came up with another 320 ‘shielding unit’ beds for people who hadn’t got that ability to restrict their movements and we moved medically vulnerable people into units.” These shielding units were operated by Crosscare, Depaul, McVerry Trust, Novas and San Kalpa. The HSE Healthlink team provided clinical support for these units.

Simultaneously, addiction services were enabled to have a 12-week waiting list for methadone cut down to three days. A maintenance and reduction course for those addicted to benzodiazepines was managed by GMQ. Separate housing for those with disruptive behavioural issues was secured and staffed by Focus Ireland. Ana Liffey Drug Project, Chrysalis and Coolmine provided inreach support for clients. Dublin Simon provided counselling services over the phone.

This intensive and collaborative approach returned results that defied expectations: “We tested as many people and up to December 2020, had 80 Covid positive cases. In early January, we had 50 Covid positive cases among clients. These are actually much lower figures than we had anticipated; we expected a much higher number of positive cases, so we’ve actually done extremely well in terms of positivity.

“By January, we had up to 206 people in shielding units, and another 150 shielding in accommodation that they had previously been in which proved suitable. In shielding units, we haven’t had any positive cases, which is a fantastic result. We have now had 130 positive cases overall, but interestingly, while we had predicted that we would have 23 deaths by April 2020, we have only had three deaths overall and the third death was someone who contracted Covid in hospital, not in homeless services. During the first surge, it was reported that not only was there low numbers of homeless presenting with Covid, but they also reported a reduction for non-Covid issues.”

O’Carroll is currently undertaking research to prove what he has seen in the response to Covid: that the melding together of healthcare, housing and addiction services can be a powerful combination in combatting homelessness.

“What I believe strongly is that uniting everyone in this mission is the key to going forward. The issue of homelessness is a justice issue and a public health issue. The factors supporting these positive outcomes are the existing homelessness services, the HSE and DRHE and a clear corporate and clinical governance structure. The collapse of the rental and hotel market was key in terms of freeing up accommodation. I think we’re lucky in Ireland to have a social inclusion directorate in the HSE, which is fairly unique in Europe and not to be underestimated,” O’Carroll says.

Concluding, O’Carroll stresses the importance of keeping the spirit of collaboration alive after the pandemic: “Going forward, to ensure we keep sight of that common mission. Housing is a priority, and we must manage the housing and rental markets to both prevent homelessness and increase housing supply. We need to remove the competition from homeless health and accommodation markets. There’s a real sense of collaboration. Often, you’re put up against each other to bid for initiative and there is a lot of competition, but Covid has brought everyone together. We have to ensure rapid access to addiction services, maintain structures that encourage collaboration and fill the gaps in mental health services.”