Circle Voluntary Housing Association: New horizons

1st August 2018

AHBs: The future of the housing sector

1st August 2018Housing Assistance Payment expansion

The Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) is a form of social housing support available to households eligible to be included on the local authority housing waiting list, including long-term Rent Supplement recipients. Its implementation, with a heavy reliance on the private rental sector, reflects what is regarded as the Government’s policy shift from “bricks to benefits”.

Under HAP, local authorities make a monthly payment to private rented market landlords on the final Wednesday of each month in order to cover a tenant’s stay for a calendar month. Recipients must locate their own accommodation, secure their own deposit and ensure that the landlord agrees to rent the property to a HAP recipient.

In return, recipients must pay a weekly rent contribution, based on the differential rent scheme, to their respective local authorities. Failure to do so results in HAP payments being suspended. Likewise, payments are subject to specific rent caps. In Dublin City, for example, the monthly rent limits allowable are as follows:

• €430 for one adult in shared accommodation;

• €500 for a couple in shared accommodation;

• €660 for one adult;

• €900 for a couple;

• €1,250 for a couple or one adult with one child;

• €1,275 for a couple or one adult with two children; and

• €1,300 for a couple or one adult with three children.

However, Dublin City Council is authorised to pay 20 per cent above these limits on a discretionary basis. Likewise, under Homeless HAP, the council may agree to pay a deposit and two months’ rent in advance as well as paying up to 50 per cent above rent limits.

The HAP scheme, which is the cornerstone of the Government’s social housing policy, is designed to be mutually beneficial to tenants and landlords alike.

HAP enables recipients to work full-time while receiving full housing support (even if their income increases) and rent contributions payable to local authorities are proportionate to household income. Additionally, a stated objective of HAP is to “help regulate the private rental sector and improve standards of accommodation” with local authorities inspecting rental properties to ensure they meet require standards.

At the same time, HAP recipients can avail of other State social housing supports, all accessible under a single umbrella – local government. Meanwhile, homeless HAP is currently available only to those registered as being homeless in Dublin.

As of 2016, landlords who rent to tenants who are in receipt of social housing support, such as HAP, are entitled to enhanced tax relief. For example, property owners can claim 100 per cent relief on mortgage interest if they agree to make their accommodation available to qualifying tenants for three years (an undertaking which must be registered with the RTB). Likewise, for landlords, payment is made to them electronically, negating the need for rent collection from HAP recipients.

It is a stated of objective of Rebuilding Ireland that “the Government’s long-term approach for assisting households living in the rental sector requiring support is through the HAP scheme and so all rent supplement recipients with a long-term housing need will transition to HAP”.

Indeed, since March 2017, HAP has been administered on a national basis, through the Housing Assistance Payments Shared Services Centre (HAP SSC), by Limerick City and County Council on behalf of the 31 local authorities and the Dublin Region Homeless Executive.

In 2018, its first full year as national customer contact, the HAP SSC, headed by Director Eoghan Prendergast, is expected facilitate a total of over €400 million in HAP transactions. As such, it is the most significant social housing rent support programme in the Government’s Rebuilding Ireland action plan. Across Dublin, where social housing need is most acute, only 1,582 HAP tenancies are currently managed across the four local authorities.

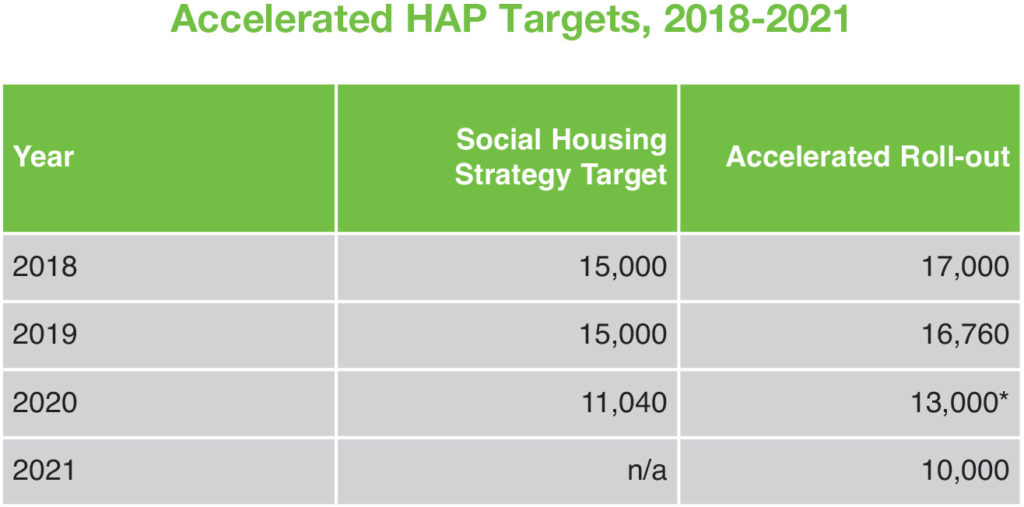

Over its phased introduction since 2014, financial transactions have increased from €600,000 to €230 million in 2017. There are currently 37,462 HAP tenancies with a yearly budget of €310 million and payments to landlords are rising by almost €1 million a month. A target of 84,000 tenancies and a budget of almost €1 billion has been set for 2021.

Tenants deemed to have had their social housing needs met are subsequently removed from the social housing waiting list and, if they still wish to be considered for social housing, are then invited to apply to be placed on the local authority’s transfer list.

However, the Public Accounts Committee has been critical of the payment of €153 million to landlords in the private rental sector last year without sufficient inspection of properties. The current rate of inspection stands at 25 per cent and, suggesting that local authorities and the Department are “not fulfilling their statutory duties”. PAC Chairman Seán Fleming stated: “For the Department to set aside 75 per cent of targets and not comply with statuary obligations is unacceptable and is something the PAC will be looking into in the next term.”

On top of this, the Home at Last report, commissioned by Dublin City Council and published by geographers Katherine Brickell, Mel Nowicki and Ella Harris from the University of London, indicates that HAP “ultimately does little to provide security of tenure or remove the prospect of homelessness in the future”. Furthermore, the report contends that “solving Dublin’s housing crisis cannot be fully realised without acknowledging the private rented sector as a major route into homelessness”.

Home at Last identifies a reluctance among landlords to engage with Rent Supplement and HAP recipients. “The linkages between the private rented sector and housing precarity are furthered by a seeming reluctance on the part of landlords to accept tenants who are on social welfare. This made finding a property via HAP extremely difficult,” it outlines.

Where there was engagement, due to the “clear imbalance” between landlords and tenants, there is “little choice but to live in a state of perpetual housing precarity, with the threat of eviction a looming presence”.