Innovative housing for wellbeing: Respond’s Brain Health Village

4th July 2024

Housing Agency CEO Bob Jordan: Rising to the housing challenge

4th July 2024Round table discussion: Bridging the funding gap to facilitate housing delivery

Beauchamps hosted a round table discussion with key housing stakeholders from across the public and private sectors to explore their perspectives on bridging the funding gap to meet the estimated €20 billion required to deliver the Government’s new target for housing delivery.

What is the true cost of delivering an average of 50,000 homes per annum?

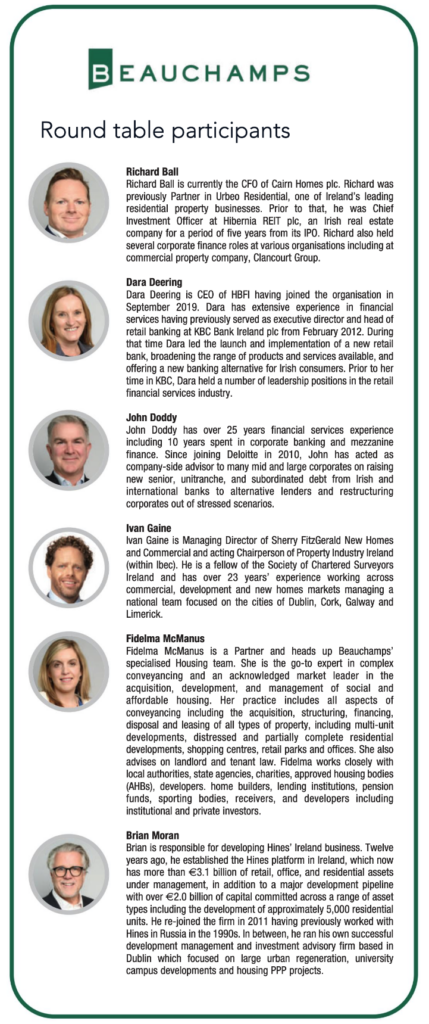

Richard Ball

While most people focus on the capital requirements, the narrative needs to change. Consider instead, from an economic perspective, the lost opportunity if we do not deliver 50,000 units each year. The housing sector must determine the socioeconomic equivalent of one unit of housing supply. We also need to question how housing is understood. If housing is deemed to be a component of infrastructure, we should create a solution to attract infrastructure investors into the market.

Dara Deering

If you consider the figures in the Department of Finance’s Report on the Availability, Composition and Flow of Finance for Residential Development, building 50,000 homes each year will require over €20 billion of development finance. No matter what way you split the State’s investment, it can only accommodate – in the Department’s estimate – 18 per cent, which means that 82 per cent of this capital must come from the private sector. One of our challenges is that there are only two pillar banks remaining in the State. While they exhibit a great appetite to lend in the market, their balance sheets can only carry limited capacity in the system. Our focus in Home Building Finance Ireland (HBFI), as a state lender, is to determine whether there is more we can do to leverage private sector capital on a more sustainable basis.

Fidelma McManus

The most significant cost is the cost of failing to deliver. Ireland’s economic growth will stall in the absence of places for people – including young professionals – to live. While the State has made progress in social and affordable delivery, we are not observing the significant delivery of housing – particularly apartments – into the private market. We must consider the State’s schemes – such as the Secure Tenancy Affordable Rental (STAR) investment scheme – and if it could be amended to unlock international capital into the cost rental delivery space.

John Doddy

From a capital perspective, the estimated cost ranges from €16 billion to €20 billion. €20 billion is a significant gross figure. However, there is existing capital within the system that can be recycled. Take then the State – which as Fidelma said, is doing a lot to bridge the viability gap – in total, it is providing between €3 billion and €5 billion. Debt makes up around 60 per cent of the balance. For viable projects, debt is available, whether from the pillar banks, Home Building Finance Ireland (HBFI), or alternative lenders. For scalable projects there is also international capital available. The key challenge, therefore, is equity. In all industries, debt follows equity. The solution is to ensure that Ireland becomes more attractive from an equity perspective and that equity is rewarded in taking on risk around development. Risk sharing between the public and private sector is part of the answer, however transferring all of the risk back to the State is not the answer and is not sustainable.

Ivan Gaine

Take the housing system in its totality. There are four elements at interplay: land, infrastructure, planning, and capital. Rather than €16 billion or €20 billion, the capital cost could be €25 billion or €27 billion because we are not simply going to leap from 33,000 homes per annum to 50,000. Instead, we must transition to the revised target. Going by the Taoiseach’s target of 250,000 homes in five years, we must deliver 60,000 or 70,000 at the backend of the cycle. Depending on how we deliver these units, the cost is arguably much greater than €20 billion per annum. In addition to the direct cost of housing and the social cost, there is an infrastructural cost in terms of connection to utilities. That is the elephant in the room.

Brian Moran

From a national perspective, the quality of debate on the cost of housing delivery has been extremely poor to date. It is great to see the State and the Department of Finance getting behind the work undertaken by the Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland, which has taken a lead in moving the debate around the actual cost of housing delivery into the realms of reality. Now we must be honest, firstly, about the number of compact, high-density units required, and secondly, about the additional costs associated with that figure.

“A political narrative is fermenting against long-term investment which is inhibiting Ireland’s attractiveness for investment.”

Fidelma McManus

The Housing Commission report also emphasises that in addition to meeting the new demand for 50,000 homes per annum, there is an existing housing deficit ranging from 212,500 to 256,000 homes. We cannot sweep that under the carpet. We must admit that we need to build those as well. As such, we can add another 25,000 to the 50,000 and the figure in the Report on the Availability, Composition and Flow of Finance for Residential Development will increase in due course.

The Housing Commission’s report also emphasises that compact growth is essential. The report found that wider societal cost of not pursuing compact growth is over €100,000 per unit. Furthermore, the report has suggested that apartments will comprise around 60 per cent of the new housing delivery target – indeed Ronan Lyons has suggested that we never need to build another house again in Ireland. By definition, this means weighting the funding requirement on a much more expensive product relative to a traditional three-bed semidetached house.

How significant is the funding gap challenge that Ireland faces in delivering the new annual housing target?

John Doddy

Considering the macro environment, Ireland should be a highly attractive location for investment. While people want to invest here, we must always be cognisant of the fact that development is inherently risky. Planning is at the forefront of these risk factors, with many international investors struggling with the risk profile of our planning system. It is a challenge to motivate investors to come into Ireland with the existing limited profit margins and when it is more likely than not that your project will face delay. We also need to foster an environment where, when a project is substantially de-risked, the equity in that project can be recycled and/or leveraged to circulate back the pipeline of new projects. In other words, efficiently use the equity already in the sector.

Dara Deering

There is a lot of access to liquidity available for viable housing delivery, but if we really want to deliver compact housing at scale, then we need to tackle the phenomenon of build to sell. We have initiatives like Croí Cónaithe, but the feedback we hear is that these are not of large enough scale to attract private debt into the market.

“If I told any pension fund that there was a consensus to align rent prices with wage growth in Ireland, they would invest immediately.”

Brian Moran

Brian Moran

If you look back to the 1980s, the average two-bed apartment in Dublin was 65m2; today it is 85m2. The average worker was earning €300 per week; today they are now earning €900. Most emphatically, if you now look at the ventilation in an apartment, in 1980 it was provided by a small plastic vent which cost €4.99; today it is provided by a €40,000 heat recovery system. We have sleepwalked, as a nation, into the highest standards and the highest costs for the average apartment in Europe.

The result is that the vast bulk of the population is priced out of the housing market, whether for buying or renting. In fact, only the top two income deciles can afford the product. We must change that. Given that we are unlikely to change standards, and land is around 10 per cent of costs and even halving that will not be enough, the best lever to use is reconsidering the tax wedge. The Croí Cónaithe and STAR schemes can help because they are a non-inflationary, intelligent approach to delivering high density development and expanding its accessibility to the wider market.

With a one-month workshop with all relevant stakeholders, and some creative thinking, this is a challenge we could overcome. We could increase the accessibility of this product to at least the six income deciles.

Ivan Gaine

The Department of Finance report is very helpful in understanding what the funding gap is, but another consideration is the mortgage market and having a sufficiently sized mortgage market. If we have another 10,000 homes added to the annual delivery target, that means an additional €4 billion in mortgage funding requirement. This involves ramping up the risk and asking banks to increase their current level of lending by up to 30 per cent. When it comes to solving the funding gap, we need to consider all tenures and all aspiring owners, renters, etcetera, and match the supply side interventions.

“One of our challenges is that there are only two pillar banks remaining in the State.”

Dara Deering

Dara Deering

We often get asked if HBFI can provide equity. We do not, but in some of the schemes HBFI funds 80 per cent of the debt. Where any third-party equity is required, there can be exceptionally low returns for developers. Often tier two developers’ balance sheets are no better off after completion of a project than they might have been beforehand. One of the questions we need to address is whether, for the scale of housing delivery required in this county, we can rely on international equity alone given the returns required.

Richard Ball

To build rental stock, we must turn on the tap to the biggest source of low-cost funding, a good example of which is European pension funds. Pension funds have a liability to their pensioners, but they are willing to invest. If they can see a business case, they will buy an investment product. The biggest impediment to this investment case right now is the 2 per cent rent cap in the rent pressure zones. If the rent cap was assigned to the tenancy and not the unit, this would allow the rent to be rebased to market rent, once the unit become vacant. Cost rental is central to a greater functioning housing market and will provide a critical pathway to reaching the overall annual targets needed.

Fidelma McManus

We must ensure that the politicisation of housing does not inflate the challenge. We had an effective long term social housing leasing model – which represented a small proportion of total delivery but was effective at attracting international private investment into the sector. To those who occupied those homes, it did not matter if the local authority owned or leased the home, because the result was a long term home for the resident. This scheme secured a massive amount of private investment in the market. In the long term, leasing is not the best investment option for the State, but it should have been wound down over five to 10 years, instead of being cut off by the end of 2025. Again, in the discourse, a political narrative is fermenting against long-term investment which is inhibiting Ireland’s attractiveness for investment. The perfect counterbalance to this would have been the continuation of long-term leasing until we have a viable alternative to attract such investment.

How can Ireland become a “welcoming home” for international institutional investors to attract the estimated €20 billion required to meet the new target for housing delivery?

Brian Moran

To reiterate Richard’s previous point, the single biggest impediment is the 2 per cent rent cap in rent pressure zones. From a fiduciary perspective, pension funds cannot allocate investment when there is no guarantee that investment returns will track their liabilities in the future. If I told any pension fund that there was a consensus to align rent prices with wage growth in Ireland, they would invest immediately. That is the solution; it is not perfect but that may solve some challenges with funding development. The weight of interest in Ireland as an attractive investment location is strong, due to our economic and demographic prosperity. If we can depoliticise some of these things, we can get to solutions very quickly.

“It is a challenge to motivate investors to come into Ireland with the existing limited profit margins.”

John Doddy

John Doddy

As a country we are particularly good at attracting FDI. Attracting investment in housing is no different to other sectors, and, in fact, we are more attractive than other countries in many sectors. The key is reducing risk and thereby attracting this FDI into our housing sector at pricing that works for the investor and end user. I agree that the 2 per cent cap in rent pressure zones is a challenge but disagree that it is the main challenge. The main challenge is the constant policy changes made to the State’s funding strategy, tax policy, and overall housing delivery strategy. By presenting a more stable and predictable outlook we will be able to attract in more investment by ensuring that prospective investors can simplify their investment case. Investors like stability and predictability. This will not only increase the flow of inward investment but will also reduce the price of that capital, as investors lower the risk premium required.

Ivan Gaine

The necessary ingredients of successful international investment are certainty, stability, infrastructure, stretch targets, and new generation of rent controls which are linked to individual tenancies rather than the unit.

Richard Ball

The Government is excellent at attracting FDI to our country, however when it comes to trying to bring international capital into the housing market, we are less welcoming. The Central Bank of Ireland changed the limit for institutional property funds on leveraging to below 60 per cent based on a case study of retail investors in another European market. It is difficult enough to obtain equity, but when changes are made to allowable leverage in regulated funds, this will reduce returns and make investors consider other alternative structures. We want the Central Bank to encourage investors to use corporate structures under their regulation as that would allow them to have better oversight on the property investment market.

“The Government is excellent at attracting FDI to our country, however when it comes to trying to bring international capital into the housing market, we are less welcoming.” Richard Ball

Fidelma McManus

AHBs are primarily funded by the Housing Finance Agency (HFA) via local authorities (CALF and P&A) and The Housing Agency (CREL). That State money is invested and ensures safe modelling. An alternative use of a portion of that money, however, could be unlocked if the State was then able to refinance money out of the HFA in the long term. What we need is money going into infrastructure which needs to be developed in tandem with housing ambitions and we need to move beyond leveraging money completely against the State.

Dara Deering

There is no doubt that the private sector has appetite to support the AHB sector, as there will always be strong appetite to lend where there is state takeout. We also need to focus on how we use state money to maximum effect, and we need to ensure that state funding is also available for infrastructure development. Ultimately, in order to ensure there is sufficient international capital available we need policy stability and mechanisms to boost confidence from an investor perspective.

In addition to current initiatives, to what extent must the State play an increasing role in terms of sharing the risk with the private sector to ensure the stability of future housing supply?

Fidelma McManus

The State has answered the call and is doing a huge amount in the social and affordable housing space. However, despite the significant support, we are observing a level of transferred risk from the private sector to the public sector, and it is important we get the balance right. The AHB sector is a voluntary sector and many of these organisations can and are taking on elements of managed risk with fantastic results in terms of housing delivery. However, given the pressing challenges with infrastructure funding, the State’s intervention needs to ensure that the most pressing challenges are the ones which are being prioritised for continued medium- and long-term delivery of housing.

“Another consideration is the mortgage market and having a sufficiently sized mortgage market.”

Ivan Gaine

Ivan Gaine

We do not have a whole-of-government approach; we have conflicting scenarios. We must examine recommendation number seven in the Report of The Housing Commission to establish a Housing Delivery Oversight Executive in legislation. DPENDR, Department of Finance, and DHLGH are the three critical departments to get this up and running and stability is the path to leveraging this.

Brian Moran

It is about long-term sustainable planning. We have had a double shock in the interest rate hike caused by the Covid crisis and the Russian invasion of Ukraine which has left the door open for the State to step in to maintain counter cyclical delivery. However, we must ensure that private investment is not crowded out by state investment. The solution is to use state funds to leverage private investment in schemes such as Croí Cónaithe and STAR to increase scale. The State needs to be conscientious of how to get private investment into the market en masse.

John Doddy

With risk transfer, we have been fortunate with the large budget surpluses achieved by the State, putting it in a position to support counter cyclical delivery. In the long term, the State needs to look at incentivising investment into the country on a balance sheet light basis – for example, via forward commitment, leases, and floors – as well as using its own balance sheet to address viability gaps and ensuring infrastructure is in place to enable housing delivery. Where the State thinks there is an opportunity to bring in capital, it can use its own leverage to maximise attractiveness.

Dara Deering

Hitherto, the approach has been right. The State was required to provide stability to deal with market shocks, such as Covid and the Russian invasion of Ukraine but now we must move to a contingent-based and targeted approach. One area that we need to scale up is in the delivery of build to sell apartments and this means expanding schemes such as Croí Cónaithe. If a developer builds 200 apartments, that does not necessarily mean they will be sold and so this is a potential obstacle. We need to give the guarantee that these units can be sold, with the long-term objective of scaling up similar schemes.

Richard Ball

While the State has allocated vast capital in the last 24 months, the biggest challenge is going from allocation to deployment. If the State can improve this transition process, then more progress will be made. There is a multitude of schemes of which awareness and knowledge is growing. This also needs to improve if value for money is to be achieved. On the private capital side, we need the State to get private capital involved in the development of these schemes. Attention now needs to focus on effective implementation of the existing schemes.