Modern methods of construction: Defining an effective Irish operating model

19th February 2024

PENDR Minister Paschal Donohoe TD: ‘Capital funding at all-time high’

19th February 2024The impact of planning and regulatory delays

Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) Senior Research Officer Muireann Lynch discusses the cost of planning and regulatory delays for the energy system.

Contextualising her research, Lynch explains that the idea for the ESRI’s paper investigating the cost of planning and regulatory delays for the energy system was stakeholders querying losses incurred in the time it takes to get energy projects connected to the grid and generating power. Lynch and her colleagues analysed electric renewable energy (RES-E) projects due to such projects being a “major pillar of energy policy, both in terms of decarbonisation and of increasing security and affordability”.

“RES-E projects face various planning and regulatory hurdles; you have to get over various jumps before you finally get your project onstream,” Lynch says. “Once you have got your planning permission, you are looking for grid connection, once you have that, you are often looking for subsidy support. The literature would suggest that delays impact on delivery and these issues are not unique to Ireland. Furthermore, there is anecdotal evidence of delays in the Irish system in terms of getting projects delivered.

“On that basis, we had a couple of research questions: what impact do the delays and regulatory setup have on delivery timelines? What are the knock-on impacts on the power system?”

The roles of various organisations had to be factored into this research, as Lynch explains. Firstly, planning permission must be obtained through the relevant local authority and/or An Bord Pleanála. The planning authorisation cycle is continuous, with a targeted decision time frame of 18 weeks, although the average time frame is 37 weeks. Grid connection is governed by EirGrid and ESB Networks, with a yearly authorisation cycle requiring applicants to enter in September of every year and a decision time frame of 12 to 15 months. Generation licenses and authorisations to construct are granted in a continuous cycle by CRU. The RESS scheme operated by the Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications makes yearly awards with a decision time frame of three months, and the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage’s authorisation cycle for foreshore licensing and leasing is continuous, with a decision time frame of 18 weeks.

“We want to consider the impact of these decisions being made faster if the time to get planning permission was reduced and also if there were an increased number of opportunities to apply for grid connection and RESS,” Lynch says, explaining the terms of the research. “We are going to track 2,000MW of approved capacity that will eventually overcome these hurdles and get built. The only question here is when this capacity will get on the grid, not if it will.”

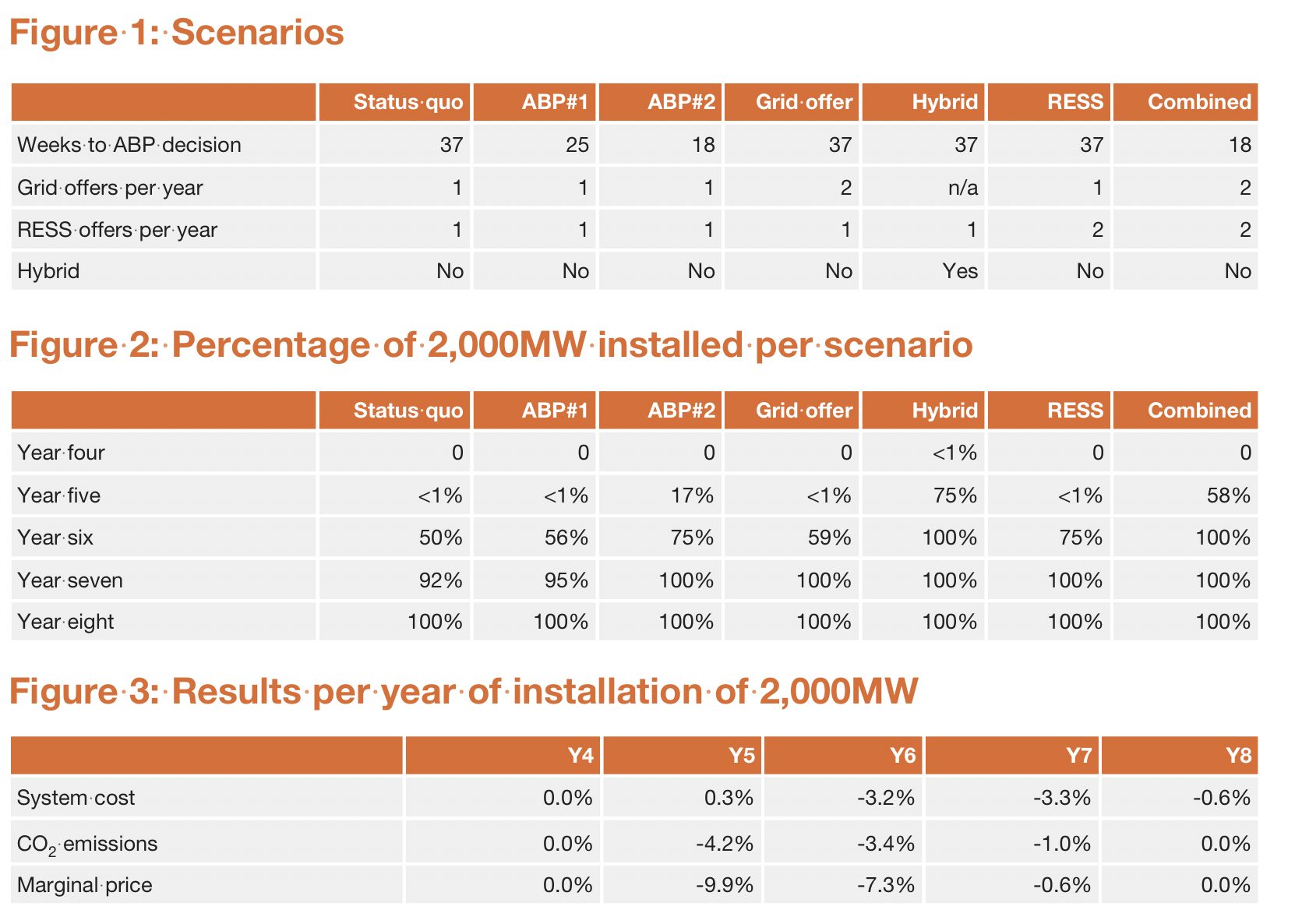

Accordingly, the ESRI constructed a number of scenarios (as seen in Figure 1), where various possibilities were considered, such as the reduction of planning decision time to 25 weeks and the targeted 18 weeks, and increases in both RESS and grid offer opportunities per year from one to two.

“This is a linear least cost optimisation model which determines the socially optimal generation and transmission expansion assuming a benevolent social planner with perfect foresight,” Lynch says, surveying the results of the scenarios examined (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). “Years one, two, and three see nothing built in any model, and in year four there was no difference between them. From years five, six, seven, and eight, we were seeing up to a 3.3 per cent decrease in system costs just from those 2,000MW getting on those few years earlier.

The research shows a possible reduction of up to 4.2 per cent in CO2 emissions with the capacity being installed in year five, a possibility made all the more important, Lynch says, “now that we are in the era of carbon budgets” due to the fact that “if you get that the 2,000MW on by year eight, you still have the extra cumulative emissions from the power system in the meantime”.

“These delays are not costless, they are having power system impacts. Increasing the number of opportunities and reducing An Bord Pleanála’s timelines would both be helpful.”

Muireann Lynch, Senior Research Officer, Economic and Social Research Institute

It is on price where the biggest impacts of these imagined reforms would be felt, with a decrease in marginal price of 9.9 per cent with the capacity delivered in year five and 7.3 per cent if it were to be delivered in year six. “There is a big impact on the difference in price getting those megawatts on those few years earlier. That can make an impact on marginal prices,” Lynch says, before offering another key footnote: “All of this was run pre-the Ukraine crisis, so if we were to re-run this under the higher fuel prices we see now, we would expect the price decreases to be bigger again.”

Planning delays undoubtedly have an impact on RES-E rollout, Lynch says, and by providing further resourcing for An Bord Pleanála and/or allowing more opportunities per year to apply for grid connections and RESS, the process can be sped up “considerably”.

Concluding, Lynch states that taking on either approach would tackle the costs and increased emissions incurred by such delays: “What I was surprised at was the impact of those delays on the costs, emissions, and particularly prices. These delays are not costless, they are having power system impacts. Increasing the number of opportunities and reducing An Bord Pleanála’s timelines would both be helpful.”