Threshold: Working to Empower Private Renters

22nd July 2020

The Housing Alliance: Placing AHBs at the centre of social and affordable housing delivery

22nd July 2020Housing at the county level

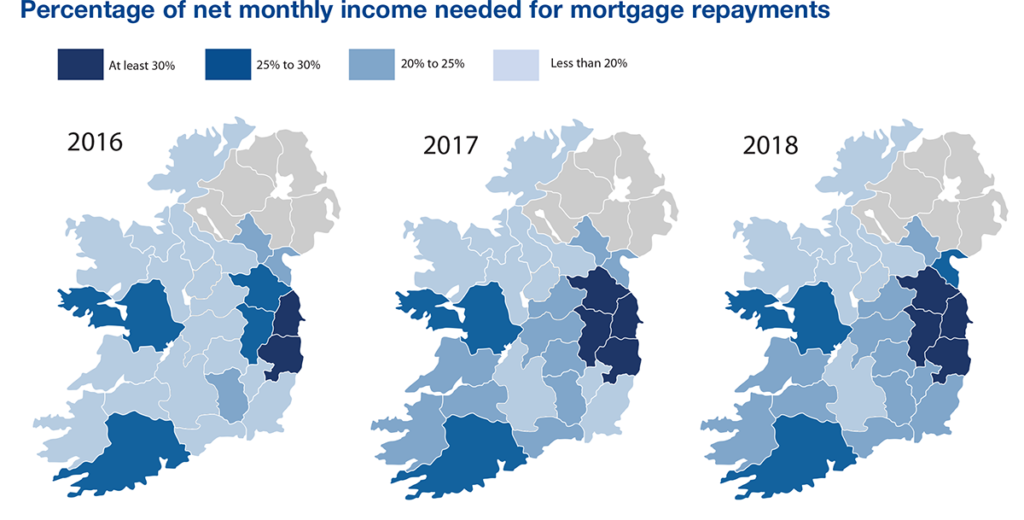

Two research reports produced by the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) illustrate a county-level analysis of housing affordability and house price sustainability, with the revelation that first time buyers in the Greater Dublin Area spend more than 30 per cent of their income per month on mortgages among the most striking findings.

One of the reports, titled ‘A county-level perspective on housing affordability in Ireland’, performed an assessment of affordability for first time buyers at the county level, finding that the mortgage-to-income ratio for potential first time buyers increased across the 26 counties of the State between 2016 and 2018. In 2018, the ratio “would have been more than 30 per cent” in Dublin, Wicklow, Kildare and Meath, while 11 of the 26 counties had a ratio at or below 20 per cent.

With regard to residual income, the report found that a first-time buyer couple “should have sufficient income left over after paying their mortgage instalments to attain at least a minimum level of consumption in all counties”. An analysis of the national trend in first time buyer prices from 2010-2018 show prices bottoming out in 2013, but then rising year-on-year every year, with 2010 levels surpassed in 2016.

However, the national picture does not give heed to the disparities that exist at the county level. Unsurprisingly, Dublin had the highest mean first time buyer price every year surveyed, with 2010 levels passed in 2014, the county’s recovery having started in 2012, earlier than other counties. By 2018, Dublin’s first-time buyer mean of €375,000 was more than three times that of Longford’s €116,000. Longford was one of only two counties to rank lowest for mean first time buyer price in the years assessed, the other being Leitrim.

Only three counties – Dublin, Wicklow and Kildare – have first time buyer means that exceed the national average of €283,000. 18 of the 26 counties have means below €200,000. Outside of the Dublin area counties, the counties with the highest means are those with cities in their own right: Cork (€255,780), Galway (€226,889) and Limerick (€213,252). The lowest means are to the north-west, in Longford, Leitrim (€119,725), Roscommon (€133,498) and Donegal (€134,344). The most notable year-on-year mean growth occurred in Laois (17.5 per cent), Sligo, Clare (both 15 per cent), Limerick (14.7 per cent) and Wexford (12.5 per cent).

Using the maximum loan-to-value ratio of 90 per cent that first time buyers face, the average new business rate for household loans (3.02 per cent in 2018) and the standard 30-year term for first time mortgages, the ESRI calculated a mortgage repayment-to-income ratio per county in order to reveal affordability at the local level. The highest of these ratios occurs in Wicklow, where first time buyers are spending 36 per cent of their incomes on mortgages; second is Dublin with 35 per cent. The only other counties above 30 per cent are the Dublin commuter belt counties of Kildare, 32 per cent, and Meath, 31 per cent.

The lowest ratios arrived at are those of Leitrim, 13 per cent, and Longford, 14 per cent. In a non-major city, non-Dublin commuter county, the ratio typically lies between 17 per cent (Roscommon, Sligo and Tipperary) and 22 per cent (Clare, Kilkenny, Laois and Waterford). The major city counties of Cork, Galway and Limerick had ratios of 27 per cent, 28 per cent and 23 per cent respectively, while Dublin-commuting Louth had a ratio of 25 per cent.

What is most notable in this research is the pace of growth in the ratio in each county, despite income levels increasing and interest rates decreasing across every county. This is said to be a result of house price growth vastly outstripping the pace of income growth.

The research does come with the caveat that the ESRI “have not explored the feasibility of borrowing by the illustrative households” and that in the higher ratio area “the implied loan-to-income ratio would likely be above the limit allowable without exemption from the current regulations” which would mean that these households would have to purchase homes at lower than the average price to comply with current borrowing limits.

House price sustainability

Using what is termed a Heat Index, the ESRI have also analysed the sustainability of house prices at the county in another research paper titled ‘Irish house price sustainability: a county-level analysis’. The Heat Index is arrived at via underlying finance theory and the user cost of capital method, giving it a “considerable advantage of having a particular theoretical structure and allows us to decompose investors’ attitudes to the housing market”. The higher a county’s Heat Index, the more unstable its market.

The research shows that rent yields are “greater than the current borrowing rate and above the rate they were during the tail end of the housing boom”. It finds that, in general, the market is well explained by fundamentals but notes that the relationship between prices and fundamentals “can change rapidly” and sharp deviations in prices and/or a change in a factor of the use cost model “could lead to prices moving out of line with the underlying value of housing”.

It is reported that there is “considerable variation” in the Heat Index across the counties, with more rural counties least likely to be at risk of overheating due in part to the failure of their house prices to recover fully from the slump that followed the 2008 economic crash. Counties in the south and south-east have the highest value on the Heat Index, but the ESRI says that “this is not be read as evidence that these markets are experiencing unsustainable inflation in prices or that the market is out of sync with fundamentals”.

The highest rental yields are reported to be in the midlands and border regions, where the steep housing price decline at the start of the decade and failure to recover have paired with recent rent increases and resulted in yields of 6.7 per cent, 6.2 per cent and 6 per cent for Roscommon, Offaly and Monaghan respectively. The lowest yields were Wexford (3.4 per cent), Kilkenny and Wicklow (both 3.4 per cent).

The Heat Index, which was above 2 in late 2009/early 2010, was found to range between -4.65 (Roscommon) and -1.36 (Wexford), indicating that house prices are recovering more rapidly than rents in Wexford. The biggest increases in the Heat Index occurred in Wexford, Kilkenny, Mayo and Sligo, while the index declined in counties such as Offaly, Meath, Cavan, Monaghan, Clare and Limerick.

Concluding, the report finds that the “Irish market does not currently display significant evidence of unsustainable house prices” and that the ESRI “do not find major difference across counties which would suggest any specific geographic areas are becoming unsustainable”.