Rise of retrofit

21st July 2020

Sophia Housing: Providing Homes, Supporting People

21st July 2020Covid-19: Bursting the Airbnb bubble

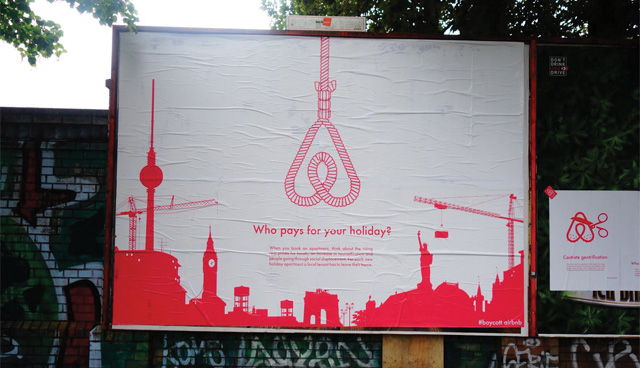

Across the world, Airbnb has been abused by would-be ‘hoteliers’ and ‘professional’ sub-letters. The platform has grown to python-like proportions, constricting private rental markets in cities around the world, but what effect will Covid-19 have?

Initially, Airbnb was conceived as a second revenue stream for people renting out their spare rooms or empty holiday homes. In short, owners could monetise their vacant and often geographically desirable space while tapping into travelling culture. With a potential for reciprocal arrangements and cultural exchange, tourists and travellers received an affordable and ‘authentic’ alternative to a hotel or hostel stay.

Today, Airbnb regards itself as an “economic empowerment engine” which “has helped millions of hospitality entrepreneurs monetise their spaces and their passions while keeping the financial benefits of tourism in their own communities”. There are in excess of 7 million Airbnb listings across over 220 countries and 100,000 cities.

With the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic and disruption to travel, it would appear that the housing empires of many aspiring rental moguls were no more rigid than a house of cards.

Data

Airbnb does not provide public data. This creates two specific challenges: firstly, it makes it difficult to understand how the platform is being used by hosts and therefore monitor the impact on the private rental market; and secondly, it hinders efforts by local authorities to ensure compliance with short-term letting legislation.

Inside Airbnb, an independent and non-commercial open-source data tool, attempts to mitigate Airbnb’s reluctance to publish data by using publicly available Airbnb listings.

Inside Airbnb utilises public reviews, minimum stay and price per night to calculate an estimated occupancy rate and the monthly income for each listing. Often Airbnb can prove more lucrative for property owners. This disproves the fallacy that Airbnb is a platform for property owners to occasionally monetise their spare room or a vacant holiday home.

In reality, entire homes and apartments are available for short-term lease (less than 14 days at a time) for most of, if not all of, the year. Quite obviously, this disadvantages city residents by removing stock from an already finite housing supply, impacting affordability and destabilising existing communities.

Using the site’s filters and metrics, it is possible to determine:

- how many listings there are in a city and their locations;

- how many houses and apartments are short-term lets;

- how frequent houses and apartments are being rented in the short-term;

- how much hosts (owners or subletters) are earning from short-term lets; and

- how many hosts are leasing multiple properties in a city.

By answering these questions, it is possible to understand the impact that Airbnb may be having on the private rental sector in a city like Dublin. For instance, it is therefore possible to determine how much of the housing stock is removed from the long-term rental market to facilitate tourists over residents while also identifying those who using the platform to run virtual hotel or hostel businesses and how much more profitable such a practice is.

Credit: David Shane.

Dublin

As of 17 July 2020, there are 9,437 Airbnb listings in Dublin. Of these, 49.4 per cent (4,663) are entire homes or apartments, while 47.7 per cent (4,498) are private rooms and 1.7 per cent (161) are shared rooms.

Around 2,566 (27.2 per cent) Airbnb listings in Dublin are recorded as highly available – that is available for more than 90 days per annum. The frequent availability of entire properties for short-term rental draws several conclusions. Firstly, it is unlikely that a property owner is present or that it is their primary residence. Secondly, this is likely to be illegal and a contributing factor to the displacement of residents.

Meanwhile, many hosts have several listings, which may be either entire properties or multiple rooms in the same property. Indeed, 43.4 per cent of Dublin Airbnb hosts have multiple listings. In such circumstances, it is likely that these are hosts are running a ‘business’ and again, are unlikely to be living in the property and are likely to be violating housing legislation.

A total of 1,908 listings (20.2 per cent) are entire properties rented by hosts with multiple properties. 811 (8.6 per cent) are entire properties which are highly available and listed by hosts with multiple listings. These listings are highly concentrated around Sir John Rogerson’s Quay, Grand Canal Dock, Temple Bar, Ringsend and Drumcondra Road.

AirDNA

According to the latest data available on AirDNA’s Market Minder, which uses “industry-leading data” to provide “valuable competitive insights on Airbnb and Vrbo rental properties” and “benchmark your short-term rentals against your competitors”, short-term rentals are up to three times more lucrative than traditional long-term rentals. Of the 3,738 active rentals listed on Airbnb and Vrbo, 69 per cent had a minimum stay of one night (34 per cent) or two nights (35 per cent). Only 2 per cent had a minimum stay of 30+ nights.

The most commonly available property has two bedrooms (39 per cent), followed by one bedroom (33 per cent), three bedrooms (14 per cent), studio and four bedroom each at 6 per cent and five or more bedrooms (2 per cent). According to AirDNA, the vast majority of properties listed are in the ‘city centre’ (834), followed by 370 in the ‘Old City’, 321 in ‘North City Central/O’Connell Street’, 236 in Phibsborough, 235 in Dún Laoghaire, and 212 in Ranelagh and Rathmines.

In the previous year, 34 per cent of listings were available full-time, with 19 per cent available for rent between 271–365 days.

Short-term rentals

Despite its founding in 2008 as a platform to facilitate short term rentals, Airbnb has increasingly encroached on private rental markets. Local authorities have responded by enhancing regulation for short-term rentals (see Figure 1).

In 2018, then Housing Minister Eoghan Murphy acknowledged that as homesharing for tourism letting gained popularity, some landlords have withdrawn properties from the long-term rental market and instead rented them as short-term lets (STLs).

Homesharing is defined as “the letting of a room or rooms in a person’s principal private residence while it is occupied by the resident”, while short-term letting is defined as “the use of a bedroom or bedrooms in a home as paid overnight guest accommodation for a continuous period of up to two weeks”.

“This is an unregulated activity, it is not homesharing as it is typically understood, and in a time of housing shortage it is unacceptable that rental homes would be withdrawn from the letting market… The reforms being presented here aim to bring homes, once available on the traditional rental market, back into typical long-term renting, to regulate for the first time STLs, and to allow homesharing to continue as it was originally meant to be – a homeowner hosting people in their own home for short periods of time,” Murphy explained.

The then Minister asserted that additional resources would be allocated to the Planning Section within Dublin City Council so that registers could be compiled, and compliance enforced. Individuals in breach of the new legislation risk criminal conviction, fines and criminal conviction.

Figure 1: Global restrictions on short-term rentals

- Amsterdam: Entire home/apartment rentals limited to a cumulative 30 days per annum.

- Barcelona: Hosts of short-term rentals are required to seek a licence, but no new licences are being issued.

- Berlin: Hosts require a licence to short-term let greater than 50 per cent of their primary property.

- London: Entire homes or apartments may only be short-term leased for a cumulative 90 days per annum.

- New York City: Unless the host is present, renting an apartment for less than 30 consecutive days is prohibited.

- Paris: Short-terms rentals are capped at a cumulative 120 days per annum.

- San Francisco: Short-term rental hosts require business registration and specific certificates, while rental of an entire house or apartment is restricted to a cumulative 90 days per annum.

- Tokyo: Short-term rental is limited to a cumulative 180 days per annum.

Regulation

As of 1 July 2019, Airbnb hosts in Ireland are subject to regulations of the Residential and Tenancies (Amendment) Act 2019. These regulations require hosts listing a room or rooms in the place where they normally reside, otherwise known as a principal primary residence (PPR), or an entire PPR, within a Rent Pressure Zone (RPZ) to register with the relevant local authority and fulfil specific obligations.

Under the new planning requirements, homesharing a room or rooms within a PPR for a cumulative period of less than 90 days per annum while the owner is absent remains permissible once registered and exempted by a local authority. However, change of use planning permission must be sought to share a PPR beyond this 90-day threshold.

Similarly, the owner of a property which is not their PPR must apply for change of use planning permission before using a property for short-term letting purposes. Meanwhile, an individual who is not the legal owner of a property must also acquire the owner’s consent before short-term letting the property.

The reforms underpinned by the Residential and Tenancies (Amendment) Act 2019 are primarily designed to mitigate the impact of the use of residential homes for short-term tourism letting on the private rental market in areas of acute housing need. Year-round short-term lets are effectively banned in private properties in rent pressure zones.

Credit: Open Grid Scheduler.

Compliance

While the Department of Housing indicated a commitment of between €750,000 and €800,000 in funding for enforcement by Dublin City Council, initial reports suggest that compliance with the new legislation among short-term let landlords and homesharers is low.

Between December 2019 and May 2020, Dublin City Council initiated more than 400 investigations into short-term property lets, bringing to total since 1 July 2019 above 600. A total of 21 enforcement notices were issue and one prosecution initiated. Staffed by 11 individuals and four enforcement offices, the Short-Term Lettings Unit has a target of 1,000 properties investigated per annum.

However, according to a report made to the council’s Planning Committee, as of February 2020, only 249 property owners had registered with Dublin City Council, a fraction of the 9,000 Dublin listings on Airbnb. At the same time, the local authority received 20 change of use applications, only one of which was approved.

Covid-19

However, according to AirDNA’s metrics the Covid-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the short-term rental market. Average daily rate (including nightly rate and cleaning) for all booked days last year fell from €166 in July 2019 to €134 in April 2020. Meanwhile, median occupancy (booked days divided by days available to rent over 12 months) decreased from 90 per cent in September 2019 to 52 per cent in March 2020. Simultaneously, median monthly revenue (nightly fees and cleaning fees over 12 months) is down from €3,331 in August 2019 to €1,361 in April 2020.

Transparent, a “Spain-based specialised data intelligence company”, indicates that the difference in occupancy between 2019 and 2020 was -91 per cent on 20 April, -89 per cent on 10 May and -63 per cent on 6 June. Estimated occupancy for 2020 year-to-date (YTD) is 38.87 per cent, almost halved from 2019 YTD which was 72.02 per cent.

Challenges

Last valued at $31 billion in September 2017, Airbnb remains privately owned, though 2020 was supposed to be the year the company went public. In September 2019, the company famously issued a single sentence statement saying: “Airbnb, Inc. announced today that it expects to become a publicly-traded company during 2020.”

Since then, Airbnb’s Extenuating Circumstances policy allows hosts and guests to cancel eligible reservations with no charge or penalty. This applies to all Covid-19 impacted reservations booked on or before 14 March for check-ins up to 15 July 2020.Airbnb acknowledged that this “will impact hosts around the world, many of whom depend on the economics they generate on Airbnb” but stood by the policy. Furious hosts responded to CEO Brian Chesky’s tweets with demands that their individual cancellation policies be honoured.

In early May 2020, in an address to his employees, Chesky confirmed that Airbnb would be reducing the size of its workforce. Revealing that Airbnb revenue for 2020 is forecasted to be less than half of that in 2019, the company raised $2 billion in capital and “dramatically cut costs that touched nearly every corner of Airbnb”.

Factoring in the uncertainty of when exactly travel would return and how this might look, redundancies were deemed necessary. Some 1,900 employees were made redundant, constituting 25 per cent of the total Airbnb workforce (7,500 employees). In Dublin, where the company employs 500 people, 320 employees are engaged in a consultation process which will see around 190 job losses (35 per cent).

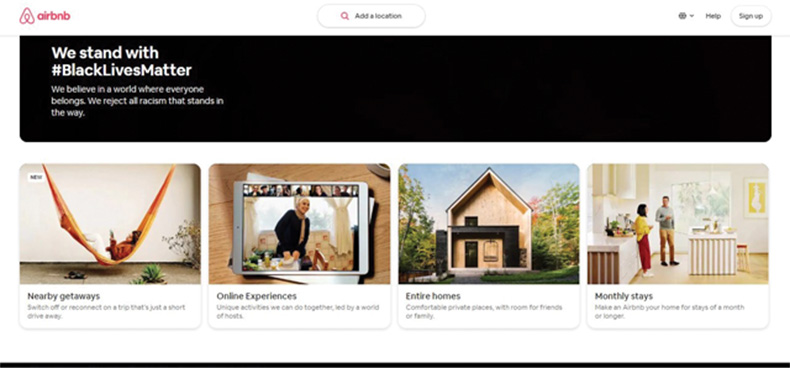

Future

Simultaneously, on Daft.ie, there has been a 40 per cent increase in the number of homes available to rent across the State in the last 12 months. With the volatility of the short-term rental market exposed, it remains to be seen if and for how long properties will return to the long-term private rental market in significant numbers.

‘Monthly stays’ are now conspicuously advertised on Airbnb.ie, though it seems likely that hosts with deep enough pockets will attempt to ride out the Covid-19 wave in their pursuit of yield. The reconfiguration of Airbnb to a primary focus on spare rooms, homesharing, and unoccupied holiday homes is doubtful.