HMO review: Changes to 2016 legislation recommended

15th April 2024

Tenant engagement strategy ‘formally paused’

15th April 2024Improved productivity in construction key to multi-market supply challenges

Labour shortages in the construction sector are posing key challenges to supply in all housing markets in Ireland and Britain, research has found.

In an extensive report analysing the Irish – north and south – Welsh, Scottish, and English residential markets, with a particular focus on their capacity to increase housing supply over the short to medium term, the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) highlights a need for changes to traditional recruitment methods.

Suggesting adaptations that include hiring trainees and apprenticeships to allow young workers to learn on the job, alongside attracting skilled workers who have left the industry to return, the research highlights that while the challenge exists across all markets, the situation is particularly acute for the Northern Ireland and British markets, where Brexit has made net immigration into the UK more difficult.

“Traditionally over the past 25 years, housing markets in Ireland and the UK have sourced a significant amount of labour from the European Union. By definition, this is now more difficult for the UK and the Northern Ireland markets,” it states.

Brexit has also had an impact on the ‘hard costs’ experienced by individual housing markets. While the Republic of Ireland has in recent years experienced higher materials and labour costs than housing markets in Britain, the rate of growth in costs in those markets has been faster, exacerbated by Brexit.

“This is putting further upward pressure on wages and prices of materials, on top of international trends generally,” the report states.

However, it is noted that Northern Ireland’s housing market has been somewhat shielded from Brexit-related cost increases in relation to materials, due to the arrangements of the Windsor Framework. This is not the case when it comes to wages, with Northern Ireland seeing the fastest rate of wage increases compared to the Republic of Ireland and the rest of the UK.

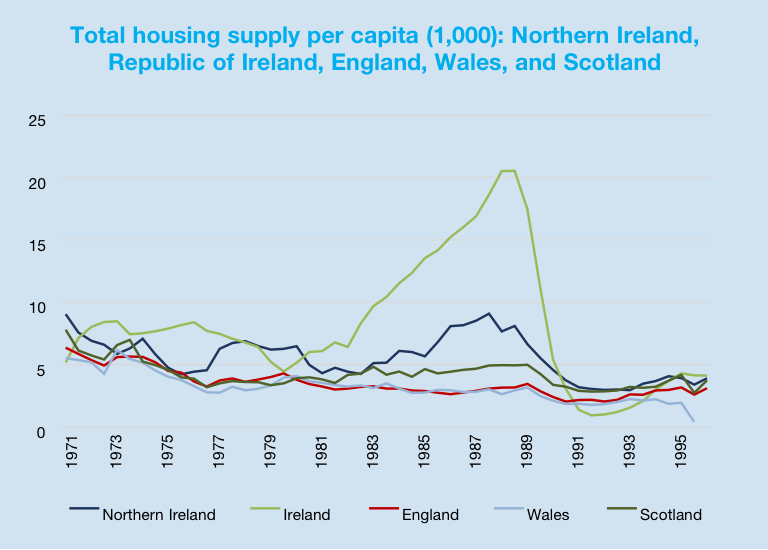

Contrasting housing supply in the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom identifies a number of substantive factors impacting the supply side of the housing market, not least production costs, regulatory environments and the economic dynamics, across the different markets.

Alongside labour market shortages, another key finding across all markets is evidence that the “traditional financial sector” no longer appears able “to provide the requisite amount of credit for the level of housing activity which has been deemed necessary to meet the underlying structural demand for housing”. The report identifies increased government investment in social and affordable stock across all markets but highlights the Republic of Ireland as the most prominent case.

From around the 1970s, governments have been less involved in the housing markets as the private sector worked to increase supply, however, the financial crash in 2008, a significant weakening of the construction sector, aligned with slow recovery and increasing demand has seen sharp rent and house price increases.

“Governments have become more active again in the housing markets, with many publishing housing plans outlining specific targets for housing supply. Given the significant fall-off in supply in Ireland, it is not surprising that the Irish Government has set the highest targets per capita across the regions discussed.”

However, recognised by the report is the fact that government housing plans usually refer to the annual increase in housing required to meet new demand due to demographic pressures, but typically do not take into account the backlog of demand due to targets not being met in the past.

Planning

While all housing markets share similarities in navigating challenges of the planning systems, the ESRI research suggests that Northern Ireland is being most hampered by a lack of standardisation in planning across local areas. Highlighting recent reform of the planning process in Ireland, the report suggests that the Scottish model, whereby local authorities when preparing local plans place a significant emphasis on consultations with interested parties and community members, might be beneficial across other markets.

“The report therefore suggests a greater degree of aggregation may be more practical in devising and implementing such development plans,” it states.

Linked to the planning system is a suggestion that housing markets in Ireland and Britain could benefit from greater regulation in the provision of land for housing, recognising the potential to reduce land prices, and lower overall production costs. In this regard, it is noted that Irish and British housing markets are “somewhat idiosyncratic” compared to other European models.

Detailed statistical analysis within the report also identified a number of key findings, namely: that compared to Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland’s housing market has a much stronger long-run price elasticity of housing supply, suggesting that investment in the Irish housing market responds more strongly to an increase in house prices than in Northern Ireland.

Additionally, Irish house prices have a significant negative relationship with housing stock, meaning that an increase in stock will lower house prices. However, the impact is weaker than in Britain, while in Northern Ireland, where increases in dwellings do not have the same deflationary impact.

Finally, the report points to analytical data which suggest that across all housing markets, house price response to changes in supply is weaker when the percentage of social housing stock is increased.