Construction at a glance

22nd July 2020

Fold Housing: Enabling its residents to age in place

22nd July 2020Rent freeze: A constitutional question

The introduction of short-term rent freeze measures during the Covid-19 pandemic have reinvigorated calls for the new Government to bring proposed long-term policy in to law, however, both Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael view such a move as potentially unconstitutional.

In late 2019, a proposal to freeze rents on all current and new tenancies won a hollow victory in the Dáíl. The then Government was defeated in the vote on the second stage of the Rent Freeze (Fair) Rent Bill but opted not to support the legislation moving onto the committee stage on the basis that it believed the measures included in the Bill could be deemed unconstitutional if challenged in court.

However, protections for renters, including a rent freeze, introduced at the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic have raised questions as to why such measures could not be a more permanent feature in tackling the housing crisis.

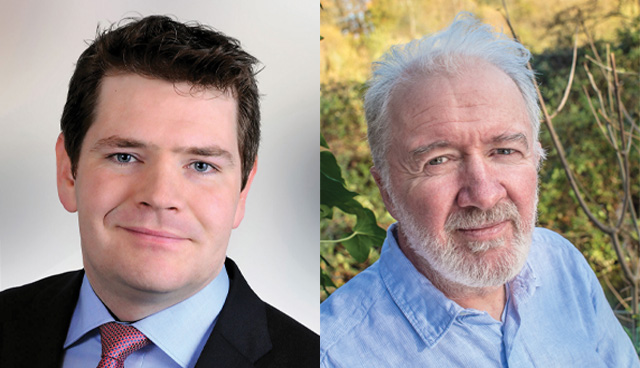

While many acknowledged that a risk of the courts finding the legislation invalid did exist, others, including Assistant Professor of Law at Trinity College Dublin, David Kenny, argued that the potency of property rights in the Constitution is often exaggerated and points to a trend of the courts giving “a lot of leeway in restricting property rights in the common good”.

Despite opposing the reading that the context of a housing crisis would be suffice to meet the legal test of taking away property rights, if undertaken in the service of the public good, the Government, by then in caretaker format following February’s General Election, did introduce rent freeze measures at the outbreak of the pandemic.

Under the Emergency Measures in the Public Interest (Covid-19) Bill 2020 an initial three month period was set out prohibiting tenants from being forced to leave a property and the increase of rents. Following an initial extension to 20 July, on 17 July Minister for Housing Darragh O’Brien’s request to extend the rent freeze and eviction moratorium on a short-term basis was accepted by the Cabinet.

Some TDs, including Sinn Féin’s Eoin Ó Broin, have called for the measures to be extended to the end of 2020 at least. Ó Broin is the architect of the Ban on Rent Increases Bill 2020, which is essentially an update of the legislation that the previous government refused to progress.

The new Bill will cap rents in existing tenancies at their current rate and new tenancy rents will be set according to the Residential Tenancies Board rent index. It proposes a three year restriction on rent increases with provision for extension by the Oireachtas but also an annual review mechanism.

The Bill also seeks to amend the Residential Tenancies Act 2004 to make it illegal to evict tenants in buy-to-let properties on the grounds that the property is to be sold.

The original version of the Bill was backed by Fianna Fáil, now the largest party of the three-party coalition Government and holders of the housing portfolio. At the time, the party stated its desire to amend the legislation to provide tax relief for small landlords. However, in the run up to the election in February it refused to commit to a “flat rent freeze” and published its own legal advice that also suggested such a move would be unconstitutional.

Some lobby groups have proposed an amendment to the Constitution to ensure the constitutionally of a rent freeze. Home for Good, the group headed up by former Barnardos Chief Executive Fergus Finlay, has asked for a referendum to be called on defining “the common good” set out in the Constitution, which states that the right to property is mitigated by the common good.

It has proposed the insertion of a new provision which declares the right to a “decent, affordable and safe home is fundamental to the common good”. The Programme for Government has set out a pledge to hold a referendum “on housing” although no details have been offered on the parameters of what will be put to citizens.

Without a change to the Constitution, Ó Broin’s new Bill is likely to face similar opposition as in 2019.

TCD’s David Kenny has previously written of his understanding that attributing the ‘unconstitutional’ label associated with the measures within the original Bill and subsequently the new Bill, is far from clear cut.

“The Constitution does not define what the common good or social justice consist in,” he says.

“This idea that the Constitution is some kind of heavy-handed block isn’t true…the only people who keep telling us that the Constitution is a problem are politicians who don’t want to take these actions and who use the Constitution as a convenient excuse.” — Eoin Ó Broin TD

“This is worked out in context, and changes with the needs of society. If challenged, the State will have to offer some common good that is served by any interference with property.”

Kenny admits that precedent exists for a possible constitutional case against the Bill but believes that general nature of the proposed rent freeze application and the context of a housing crisis is grounds for an argument against it.

Highlighting that “context is king” the constitutional law expert says that the courts would have to consider the particular objectives of the law and the current social problems it is designed to address.

“The scope and scale of the current housing crisis, and the fact that this is a time-limited measure that will not indefinitely restrict rights, would suggest the law could be upheld under this test,” he wrote in the Journal.ie in December 2019.

Adding: “I cannot think of any Supreme Court precedent on property rights in the last 20 years that would suggest the courts would invalidate a measure such as the one under discussion.”

Interestingly, Kenny also highlights a presidential power, which has never been utilised, that allows the President to refer any bill to the Supreme Court to test its constitutionality before he signs in into law.

Undoubtedly, those in favour of the new Bill, to be brought forward by Ó Broin, will seek to highlight the existence of this power given the Government’s concerns.

Talking to the Housing Magazine, Ó Broin says: “The issue isn’t that things are or aren’t unconstitutional, the issue is that if you do it in a particular way, the chance of it being deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court are greatly increased.”

Highlighting Part V of the Planning and Development Act 2000 which says that 20 per cent of any private development would be purchased at a discount by the relevant local authority, as a potential precedent for accepting the Bill, he says: “It ruled that as long as it’s fair, proportionate and in accordance with the clear social policy needs and is done in the interest of the common good, then the Constitution allows for a very wide range of limitations on the use of private property and the ownership of private property.

“This idea that the Constitution is some kind of heavy-handed block isn’t true…the only people who keep telling us that the Constitution is a problem are politicians who don’t want to take these actions and who use the Constitution as a convenient excuse.

“Is it possible to go in and sequester people’s property? Of course not. But it is possible to constrain how parts of a property are used, managed or sold to ensure, for the greater good, that regular people with good jobs can access affordable accommodation.”