The Housing Alliance: Placing AHBs at the centre of social and affordable housing delivery

22nd July 2020

Will the Programme for Government really deliver on Housing?

22nd July 2020Housing Shock

Speakers at the virtual launch of Rory Hearne’s Housing Shock included: Leilani Farha, former UN Special Rapporteur and Director of the Shift Global Right to Housing; Peter McVerry, Homelessness campaigner; Michelle Norris, School of Social Policy, UCD; Mary Murphy, Maynooth University; and Vincent Browne, retired broadcaster.

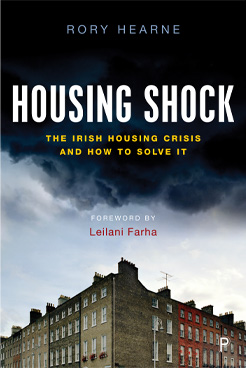

The unprecedented housing and homelessness crisis in Ireland is having a profound impact on ‘Generation Rent’, the wellbeing of children, homelessness, worsening wider inequality and threatening the economy. Rory Hearne, assistant professor in social policy with Maynooth University synopsises his recently published book, Housing Shock: The Irish housing crisis and how to solve it.

My new book, Housing Shock, explains the origins of the current crisis and macro-level changes in Irish housing policy, from strong state support for social and affordable housing to neoliberalism and financialisation. It also details the way in which the financialisation of housing has unfolded in Ireland through NAMA and real estate investment trusts (REITs).

It brings to the fore the perspectives of those most affected by the crisis, new housing activists and protesters whilst providing innovative global solutions for a new vision for affordable, sustainable homes for all. And it points to hopeful aspects in the new civil society housing protest movements in Ireland. It also details a role for academics and policymakers in social change around housing.

The Covid-19 pandemic has shown the central importance of secure, affordable, decent standard homes and housing to our lives. The message to prevent the spread has been to ‘stay at home’. But Covid-19 has also laid bare the structural problems, inequalities and dysfunctions of our housing system. Home is not a place of safety or prevention for the tens of thousands who are homeless, in emergency accommodation, direct provision, or the ‘hidden homeless’ living in overcrowded and substandard housing. The importance of housing as a social determinant of health has never been clearer.

The pandemic shows us the failings of the dominant housing policy paradigm that has treated housing as an investment asset rather than its vital role as a home that can ensure the health and dignity of those living in it. We have seen hundreds of homes, previously used as short term tourist lets, become available to rent and used to house those homeless. It begs the question why these were not properly regulated before now?

The Covid-19 downturn could still cause a tsunami of evictions if the temporary ban on evictions is not extended for at least three years and supports for tenants and homeowners including rent and mortgage write-downs are provided. It will be crisis heaped upon crisis.

In Housing Shock, I have identified such structural problems in our housing system, including the overreliance on the private market and global investors to provide housing.

Housing was a key issue in the general election and there was a clear demand for change around policy. Unfortunately, the Programme for Government, while containing some positive elements, is generally inadequate in terms of trying to address the crisis, because it does not make a major shift in housing policy. Indeed, it appears to be following the previous government’s failed Rebuilding Ireland housing plan.

At the heart of that, essentially, it was trying to incentivise the private market, subsidising private developers, and attempting to incentivise real estate funds to build housing. But the private market doesn’t work to provide affordable housing. And the public aspect of it, the building of housing by government, by local authorities, by housing associations was very minor.

In the new Programme for Government, the incoming government has set out to provide 50,000 social homes, but it is not clear how many of those will be built or will come from the private rental market.

Broadly, the major failure of housing policy in Ireland is that we have relied on the private market. We must shift to the idea of building public housing, not simply social housing but also cost rental housing and affordable housing, for mixed income families as well as people who are renters.

The new Government must develop a new housing plan to replace Rebuilding Ireland. At the heart of this should be “a green new deal for housing that provides affordable sustainable homes and communities for all”. This would be a new national housing plan, setting out how the State will guarantee a sufficient supply of affordable, secure, high quality sustainable housing.

At its core would be the aim to bring Ireland’s public housing stock (currently just 9 per cent of all housing is social housing) up to levels similar to countries with the most successful housing systems such as the Netherlands (where 30 per cent of housing is social housing) and Austria (where 43 per cent of housing in Vienna is public housing).

This would be based on the gamechanger of a new form of public housing that is available to both low- and middle-income households. A dedicated Affordable Sustainable Homes Building Agency should be created as a public enterprise body to deliver this model and ensuring the building of between 20,000 and 30,000 new public affordable and sustainable homes every year, for the next decade, alongside a major retrofitting programme.

This would provide a major employment and economic stimulus and deliver climate targets. Borrowing to build public housing and retro-fitting is a long term economic and social investment – not a cost – and better value for money than social rent payments to private landlords. Planning and housing design will also need to change incorporate new living requirements such as sufficient indoor and outdoor space in homes, green spaces, and community spaces.

We must do something radical to end Ireland’s housing dysfunction and repeated housing crashes and crises. The new housing model should be underpinned, as I set out in Housing Shock, by the right to housing as the foundation of housing policy and law. This means the right to adequate, affordable, secure housing must be enshrined in our constitution and law in order to ensure the State, and whatever government is in place, is obliged to ensure every citizen has access to a home.

A referendum is clearly required to insert the right to housing into the Constitution. This would balance property rights and provide the framework to provide protections for tenants such as removing clauses on evictions, also enable taxing vacant land, compulsory purchase orders (CPOs), taxing REITs, and provide an obligation on the State and local authorities to house homeless families and individuals within a short time frame. This is essential for eliminating (not merely reducing) homelessness. There needs to a plan and steps to end homelessness. This must be an immediate ambition.

The failure to address persistent housing issues has made society even more vulnerable to pandemics and economic crisis. Housing is fundamental to our wellbeing and a housing system that ensures everyone has an affordable secure home is beneficial for all – rich and poor – as it better protects the whole of society and economy. Achieving this is a political and societal choice. We are in a time that necessitates paradigm shifts in policy and action. Political vision and bravery on housing is required. Housing Shock asserts that we can and that we must do it.